Table of Contents

(Based on original Linux Foundation documentation, revised with permission; revisions as of 11/08/14)

OpenChain Certification Proposal

This short proposal concerns an approach to open compliance certification. The goal is to certify that software suppliers have effective measures to assure compliance with open source license obligations when they incorporate free and open source software (FOSS) in products for external distribution.

The proposal presents some general notions about certification to frame future discussions about certification; a short look (in Appendix C) at the SEI and ISO 9001 models for comparison purposes; and an outline of the compliance certification proposal. The certification proposal presents a first take at a compliance reference model, a description of alternative three-level and single-level certifications, and initial ideas on a certification appraisal methodology.

General Ideas on Certification

Certification efforts share certain common properties:

- A purpose or motivation for certification

- A standard or reference model to certify against

- A certification or appraisal methodology

- A certificate designating the subject has passed certification

- An objective certifying process (self-certification vs. third party certification)

Role players in a certification scenario typically include:

- Sponsors demanding that their suppliers be certified

- The suppliers to be certified

- A group that creates and maintains the certification model or standard and builds consensus and support for it

- Agents that perform the certification appraisal. (If the group that created the certification model is not the sole appraiser, the group may accredit agents qualified to perform appraisals. Consider using the IEC if this is an ISO-approved standard.)

- Sources that deliver supporting services such as training and consulting on the subject matter of the certification

An important principle underlies the notion of certification: that process matters, i.e. a repeatable and systematic process results in an outcome of expected quality and consistency. So an appraisal certifies a supplier’s process as a predictor of eventual success, reducing the need to rely only on testing the supplier’s ultimate product or service. Generally, certifications address quality or conformance to a standard rather than business efficiency. By intentional design, as ongoing testing results consistently in validation of the supplier’s process as producing quality results, there is an opportunity for such results to be trusted by downstream recipients.

Open Compliance Certification

The OpenChain Working Group with support from the Linux Foundation now has an opportunity to create a new certification program to help drive companies’ open compliance initiatives. The purpose or motivation for open compliance certification is to increase commitment and diligence toward achieving compliance with FOSS licenses. If certification is to gain momentum, Linux Foundation member participating OpenChain companies must step forward and require or incentivize their supply chains to attain certification as proof of their commitment and adherence to effective compliance practices.

Certification will recognize that companies have established processes, procedures, tools, training, staffing, and infrastructure needed to execute compliance responsibilities on a routine and systematic basis. The OpenChain Working Group Linux Foundation will design a certification seal or emblem to recognize those companies that have achieved compliance certification.

The OpenChain Working Group Compliance Program will take a leadership role in establishing the compliance reference model. The Self-Assessment Checklist published November 1, 2010 provides a strong foundation for the model. (See References section below.) A first approximation of the compliance reference model is incorporated in Appendix A, below. Depending on the wishes of the LF membership and community, the model could be organized either as a multi-level model (ala CMM) or a single-level model (certified/not certified) in the mode of ISO 9001. (See Appendix B, below, for discussion of the multi-level and single-level certification approaches.) Opportunity should be afforded for community input to the model formulation in order to increase buy-in and adoption.

An appraisal methodology can be defined, based again on the Self-Assessment Checklist and the reference model (once solidified). by developing further the criteria and checklists in the appendix. The OpenChain Working Group Open Compliance Program will take the lead on developing performing appraisals, but other professional services companies in the compliance space would be the intended provider of could also perform appraisals based on the reference model and appraisal methodology description. The Linux Foundation’s open compliance training courses and collected white papers, augmented by Linux Foundation our consulting services, may will serve as primary educational resources for companies preparing to undergo certification.

References

Self-Assessment Checklist, http://www.linuxfoundation.org/programs/legal/compliance/self-assessment-checklist

Standard CMMI Appraisal Method for Process Improvement (SCAMPI) Lead Appraiser Certification, http://www.sei.cmu.edu/certification/process/scampi/index.cfm

Appendix A

First Approximation of a Compliance Reference Model

The compliance reference model will consist of a set of goals and supporting practices. In appraising whether the goals have been met, auditors typically look at the supporting practices to see whether they have been performed or instantiated. Six goals and their supporting practices are outlined below. The complete reference model will define additional levels of detail and alternative supporting practices, while the appraisal methodology will guide auditors in what to look for and how to determine whether or not a goal has been met. Part of the certification includes the requirement that those employees who need to adhere to the process be trained on it. Additionally, as the process is dependent on such employees’ ability to know when the process is triggered (e.g., when certain open source software is used) such employees need to be trained on a consistent set of topical areas that are incorporated into the educational materials, that we propose also form part of the certification criteria.

Outline of Compliance Reference Model

G = Goal

SP = Supporting Practices

C = Criteria for supporting practices

(see charts below for original version)

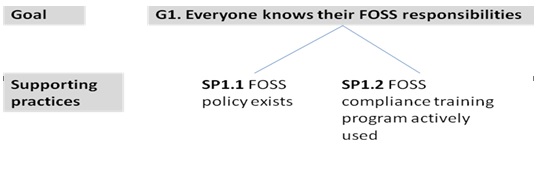

- G1: Everyone knows their FOSS responsibilities

- SP1.1 FOSS policy exists

- C1.1.1 Written

- C1.1.2 Internally available

- C1.1.3 Content must include:

- distribution of open source

- internal use for code generation

- requirement to comply with licenses

- utilization of a FOSS approval process

- SP1.2 FOSS compliance training program actively used

- C1.2.1 Required for all relevant employees, including:

- software developers

- software program managers

- software procurement roles

- C1.2.2 Content:

- Identify FOSS

- FOSS concepts and obligations

- How to adhere to FOSS approval process

- C1.2.3 Delivery method

- In-person, online (JL: should we dictate what format the training delivery method should be? Is this to mean it can be in either in-person or online - or needs to be in both formats?)

- C1.2.4 Compliance and attendance (JL: compliance with the training? might not want to use the word “compliance” here as it is more associated with license compliance?)

- Recordkeeping

- Reoccurring training

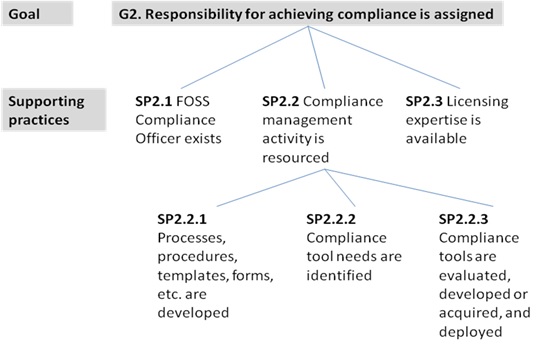

- G2: Responsibility for achieving compliance is assigned

- SP2.1 FOSS Compliance Officer exists

- SP2.2 Compliance management activity is resourced

- SP2.2.1 Processes, procedures, templates, forms, etc. are developed

- SP2.2.2 Compliance tool needs are identified (JL: do we want to specifically say “tools”? Are tools always required, e.g. small companies who still want to use these guidelines?)

- SP2.2.3 Compliance tools are evaluated, developed or acquired, and deployed

- SP2.3 Licensing expertise is available (JL: recommend putting this as first SP here)

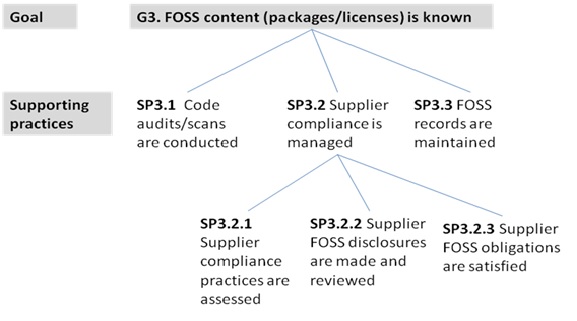

- G3: FOSS content (packages/license) is known consider making this G2?

- SP3.1 Code audits/scans are conducted

- SP3.2 Supplier compliance is managed (JL: define who a supplier is; what if the company in question is situated to not really have suppliers, do they still have to comply with these goals?)

- SP3.2.1 Supplier compliance practices are assessed

- SP3.2.2 Supplier FOSS disclosures are made and reviewed

- SP3.2.3 Supplier FOSS obligations are satisfied

- SP3.3 FOSS records are maintained (JL: move up in list here)

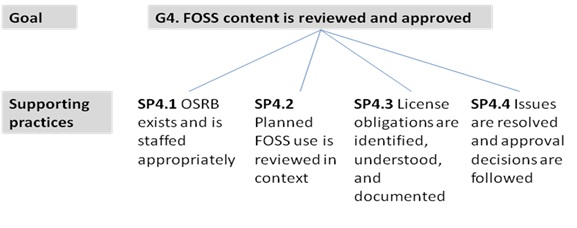

- G4: FOSS content is reviewed and approved

- SP4.1 OSRB exists and is staffed appropriately

- SP4.2 Planned FOSS use is reviewed in context

- SP4.3 License obligations are identified, understood, and documented

- SP4.4 Issues are resolved and approval decisions are followed

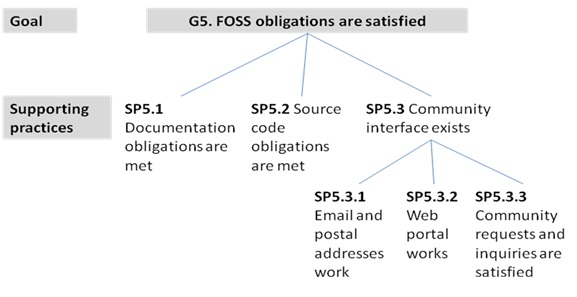

- G5: FOSS obligations are satisfied

- SP5.1 Documentation obligations are met

- SP5.2 Source code obligations are met

- SP5.3 Community interface exists

- SP5.3.1 Email and postal addresses work

- SP5.3.2 Web portal works

- SP5.3.3 Community requests and inquiries are satisfied

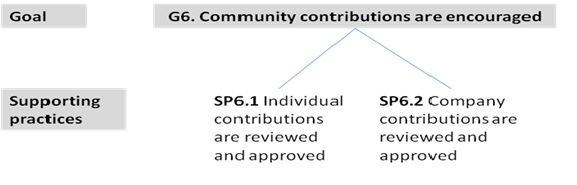

- G6: Community

contributions are encouragedengagement is understoodSP6.1: Individual contributions are reviewed and approvedSP6.2: Company contributions are reviewed and approved- SP6.1: Community participation is reviewed and approved.

Appendix B

Multi-Level vs Single-Level Compliance Certifications

Multi-Level Compliance Certification

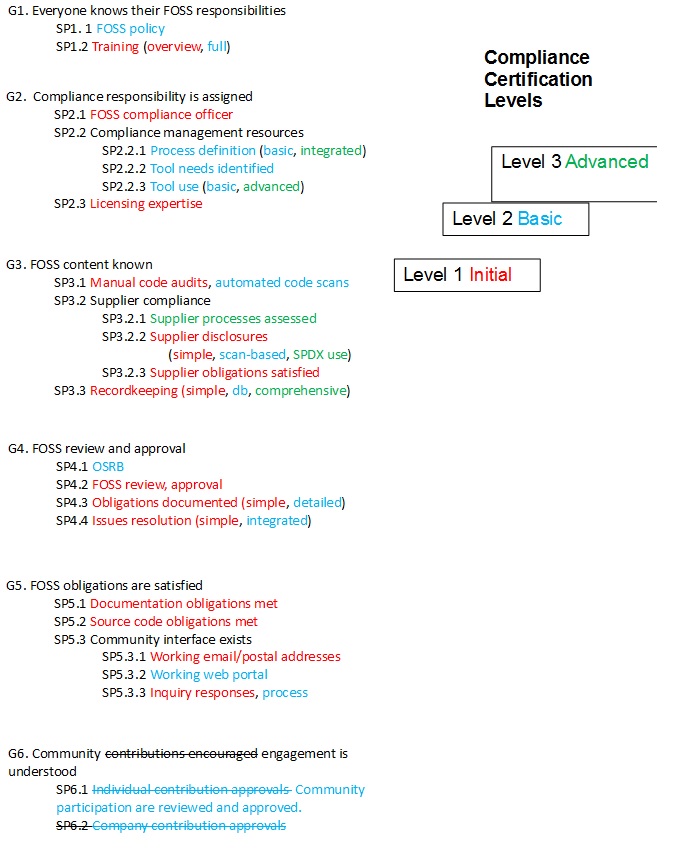

The following text refers back to the compliance reference model presented in Appendix A, above. Inasmuch as the reference model will likely evolve, so too would the ideas presented here on levels of compliance process maturity. Community input will influence assignment of capabilities to maturity levels. Additional detail in the model will also influence the determination of maturity level. For instance, SP3.2.2 (“Supplier FOSS disclosures are made and reviewed”) could be appraised at different levels of maturity depending on the supporting practices involved. A simple supplier disclosure on paper or in a spreadsheet might characterize an Initial level of maturity; using the output report of an automated scanning tool’s analysis of the supplier’s source code might characterize a Basic level of maturity; and an SPDXTM-based bill of material prepared after a scanning tool’s analysis might characterize an Advanced level of maturity.

A three-level description of compliance process maturity for purpose of certification might look like this (using the nomenclature introduced in Appendix A):

“Initial”: SP1.2 (training [overview]) SP2.1 (compliance officer) SP2.3 (licensing expertise) SP3.1 (manual code audits) SP3.2.2 (supplier disclosures [simple]) SP3.2.3 (supplier obligations met) SP3.3 (records kept [simple]) SP4.2 (reviews) SP4.3 (obligations documented [simple]) SP4.4 (issues resolved [simple]) SP5.1 (documentation obligations met) SP5.2 (source code obligations met) SP5.3.1 (email and postal addresses) SP5.3.3 (responds to inquiries)

“Initial” maturity will be characterized by ad hoc actions led by individuals with prior FOSS community involvement. These individuals may struggle to overcome organizational inertia, indifference, or resistance to compliance efforts. Actions, usually manual in nature, are taken to document FOSS inclusion and to satisfy obligations. Recognition of FOSS and satisfaction of obligations will often be incomplete or inaccurate.

“Basic”: Initial maturity plus SP1.1 (policy) SP1.2 (role-based training) SP2.2.1 (process documentation [standalone]) SP2.2.2 (tool needs identified) SP2.2.3 (tool use [basic]) SP3.1 (automated code scans) SP3.2.2 (supplier disclosures [scan-based]) SP3.3 (records db) SP4.1 (OSRB) SP4.3 (obligation playbooks) SP4.4 (integrated issue tracking) SP5.3.2 (web portal) SP5.3.3 (community inquiry process) SP6.1 (individual contributions process) SP6.2 (company contributions process)

“Basic” maturity will be characterized by systematic efforts to document processes and create infrastructure for repeatable performance of compliance actions. Broad actions will be taken to educate the organization about compliance responsibilities and processes. Tool needs will be identified and plans created to evaluate and acquire tools for FOSS identification and compliance management. Recognition of FOSS inclusion and satisfaction of obligations will become the norm, though exceptions and process “escapes” may continue to occur.

“Advanced”: Basic maturity plus SP2.2.1 (integrated process documentation) SP2.2.3 (tool use [advanced]) SP3.2.1 (suppliers’ processes assessed) SP3.2.2 (SPDXTM use) SP3.3 (integrated recordkeeping)

“Advanced” maturity will be characterized by integration of compliance actions into the company’s business processes, tools, and systems. Compliance will become a fundamental aspect of doing business for the company. Recognition of FOSS inclusion and satisfaction of obligations will become routine. Assignment of capabilities to certification levels can be summarized in the following figure:

Single-Level Compliance Certification

A single-level compliance model for purpose of certification would correspond to the “Basic” maturity level described above. Practices at the “Basic” level are those required to achieve compliance on a routine basis, regardless of productivity or efficiency considerations. Certification is intended to communicate that a sponsor can rely on a supplier’s compliance practices.

While the capabilities implied by the “Advanced” maturity level above may be desirable for multiple reasons, those steps may not be necessary to achieve compliance and provide the desired level of trust and reliance. Appraisals would closely examine the evidence presented and responses from interviewees to determine whether compliance processes are working effectively. Failure to achieve compliance on a routine basis may be evidence that “Advanced” practices, in fact, are needed.

Appendix C

A Comparative Look at Popular Certification Models

Software Engineering Institute (SEI)

By the early 1990s, many large weapons and C3I contracts for the United States Department of Defense (DoD) had failed to achieve their objectives due to software problems. As a result, the DoD decided to fund a Software Engineering Institute, which it awarded to Carnegie Mellon University. Under the leadership of Watts Humphrey, the SEI sponsored development of a software Capability Maturity Model (CMM) to help development organizations improve their software processes. The CMM (a five-level model) was the outcome of a community effort involving hundreds of contributors. In concert with release of version 1.0 of the model, the SEI developed a self-appraisal methodology and then trained and authorized a first cadre of appraisal facilitators. The original CMM consisted of a number of key process areas, each with a small number of goals and supporting practices whose use typically demonstrated achievement of the goals.

Although the SEI originally focused on self-appraisals to encourage frank and confidential internal discussions about improvement needs, eventually many DoD contract sponsors required that bidders provide evidence of (at least) Level 3 maturity. These funding agencies required an appraisal, conducted by a government-approved appraisal team, as part of the award process.

Over time, the SEI’s model was recognized for the soundness of its software engineering principles and its ability to drive process improvements. A large community of industry and government people coalesced around its guidance. The model itself has continued to evolve and has spawned additional maturity models, as well as a cottage industry of consultants offering appraisal and training services.

ISO 9001

The ISO 9000 family of standards address quality management systems and are published by ISO, the International Organization for Standardization. ISO 9001 covers engineering and product development activity. Reportedly, over one million companies worldwide are independently certified as having met the ISO 9001 standard. Certified companies typically display their ISO 9001 banners and emblems proudly as a distinctive mark of competitive excellence.

ISO itself does not certify companies. Certification agents, authorized by accreditation bodies in individual countries, appraise companies applying for ISO 9001 certification.

An ISO 9001 audit results in a pass/fail outcome, rather than a maturity level as in the SEI model. Audits result in lists of corrective actions to be taken. Major “discrepancies” can result in audit failure; minor “discrepancies,” no matter how numerous, will not stand in the way of passing the audit. Audit follow-up typically involves corrective actions whose completion must be reported to the certification agent. Re-certification must occur periodically, typically every three years.

Appendix D

Initial Ideas on Certification Appraisals

When performing certification appraisals, auditors must look for evidence that a practice is routinely and repeatedly performed and that it accomplishes its intended purpose. Typically, auditors ask to see evidence that a practice has been used, for instance, status reports, action item lists, meeting minutes, scan reports, policies and procedures, forms (both templates and completed examples), checklists, and so on. Auditors interview the people performing the compliance practices, asking them questions such as:

- What is your role and responsibility?

- What inputs are needed to perform your actions? Are those inputs routinely provided?

- What outputs do you produce? Who acts on those outputs?

- What are the challenges or issues in performing your role? What could be improved?

The goal in interviewing is to identify whether systematic processes, in fact, are used and whether those processes work effectively. Auditors should distinguish between a practice that exists as a paper definition from one that is routinely used and relied upon to achieve compliance. In the parlance of the original SEI training, auditors assess whether an organization has institutionalized a process capability by examining:

- Commitment to perform (as evidenced by policy and documented process requirements)

- Ability to perform (availability of skilled staffing, resources, and funding)

- Activities (the key supporting practices used)

- Measurement and analysis (measures and metrics used to monitor process execution)

- Verification (audits and assessments used to confirm the right things were done)

Appraisals will take into account the scope and nature of the appraised company’s products and development efforts to gauge the appropriateness of compliance practices. The final report of the certification appraisal will indicate goals fully and partly satisfied, along with process strengths and weaknesses and corrective actions to be taken. If an appraisal of a supplier is being performed at the request of a sponsor, an agreement will be reached whether to provide the final appraisal report to the sponsor as well as to the supplier.

In defining a methodology for compliance certification appraisals, these ideas will be elaborated and operationalized to create an effective, repeatable, and consistent certification process.

Comments

Enter comments here